Equity X-Ray: In-Depth Research #26

The New Heavens: An Investor's Bible for the Space Economy

Introduction

There was once a period in history when the sky at night was a painting board for gods and a timekeeping device for farmers. It was a domain of mystery and the unknown, a vast, silent blackness filled with the twinkling jewels of far-off fires. While we mapped the stars’ configurations to determine the coming of seasons and to guide us through the vast oceans of the world, the economic system of the stars produced no other dividends than in the form of awe and amazement. Those times are gone.

The present, however, has brought forth a new type of energy into the cosmos. The vast blackness that previously had remained unbroken is today punctuated by thousands of miles of virtual high-speed information highways. The constellations are now being remapped not by poets or artists, but by engineers designing the satellite networks that will be used to send information across the globe. The craters that remain from the Moon’s original volcanic activity are now viewed as survey areas for possible mining opportunities, landing sites for robotic delivery vehicles, and the like. The stars have now been designated as zones of use for industrial, commercial, and military purposes. A new economic system has developed which uses the concepts of gravitational pull and orbital motion, window of opportunity and cost of travel (delta‑v) to generate wealth and profit. It is an economic system that has been developed upon the most inhospitable frontier that man has yet to encounter.

This is not a story about a remote future. It is occurring right now above your head in the frigid vacuum of space. And for those individuals who can learn to interpret the newly created celestial map, it may represent the largest wealth-creating event of their lifetime.

This article is your roadmap.

🌱 Support Our Work: Buy Us a Coffee🌱

Your small gesture fuels our big dreams. Click below to make a difference today.

The emergence of the space economy did not begin with a business plan, but rather with a noise — a simple electronic “beep-beep-beep” emanating from the void.

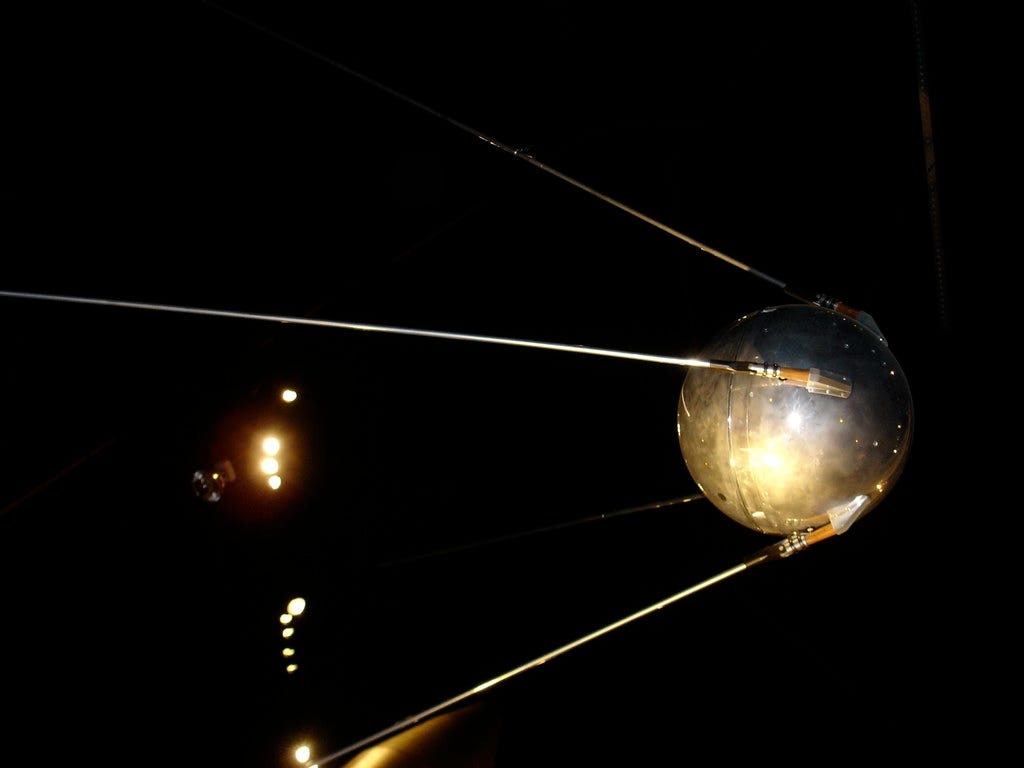

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, a shiny metal orb no larger than a beach ball. It was a marvel to the world and a wake-up call to the United States. It was the start of the Space Race. The faint, repetitive signal broadcasting from an adversary’s satellite flying freely above American soil sent a shock wave through the country. The sky that had been a symbol of endless opportunity was now a vulnerability.

In less than a year after the launch of Sputnik 1, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was born, and the best and brightest scientists and engineers in America were called upon to enter a technological war against the Soviet Union. The objective was not profit, but to assert ideological superiority. Each launch, each achievement, was a piece of the Cold War being fought globally on a grand scale. When Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet cosmonaut, became the first human in space in 1961, America was dealt a significant blow to its national prestige. President John F. Kennedy addressed the U.S. Congress and proposed a challenge of such enormity that it seemed almost impossible: to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth before the end of the decade. His statement became famous when he said, “We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

This was not the language of commerce. It was the language of a superpower marking a boundary in the celestial expanse. The Apollo Program became one of the largest peacetime efforts in the history of humanity. At its peak, the program employed over 400,000 workers and was supported by over 20,000 corporations and educational institutions. The Apollo Program was a centralized, government-run undertaking.

The costs associated with the program were justified by national security and pride, but the long-term benefit was an unintended one. The need to reduce the size of a computer large enough to occupy an entire room into a device small enough to fit into a spacecraft accelerated the development and adoption of the integrated circuit: the microchip that is the foundation of our modern digital society. Software for the Apollo Guidance Computer used read‑only core rope memory for flight programs and erasable magnetic core memory for data; the rope memory could not be altered in flight. The need to track Apollo spacecraft resulted in a global tracking network and helped pave the way for later satellite navigation; however, the Global Positioning System (GPS) used today was developed later by the U.S. Department of Defense, with the first satellite launched in 1978. Fire-resistant materials developed for use in space suits and spacecraft during the Apollo era have contributed to protective gear used by firefighters on Earth. These innovations formed an early, unplanned return on investment resulting from the pursuit of space — a result of the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union, not the reason for it.

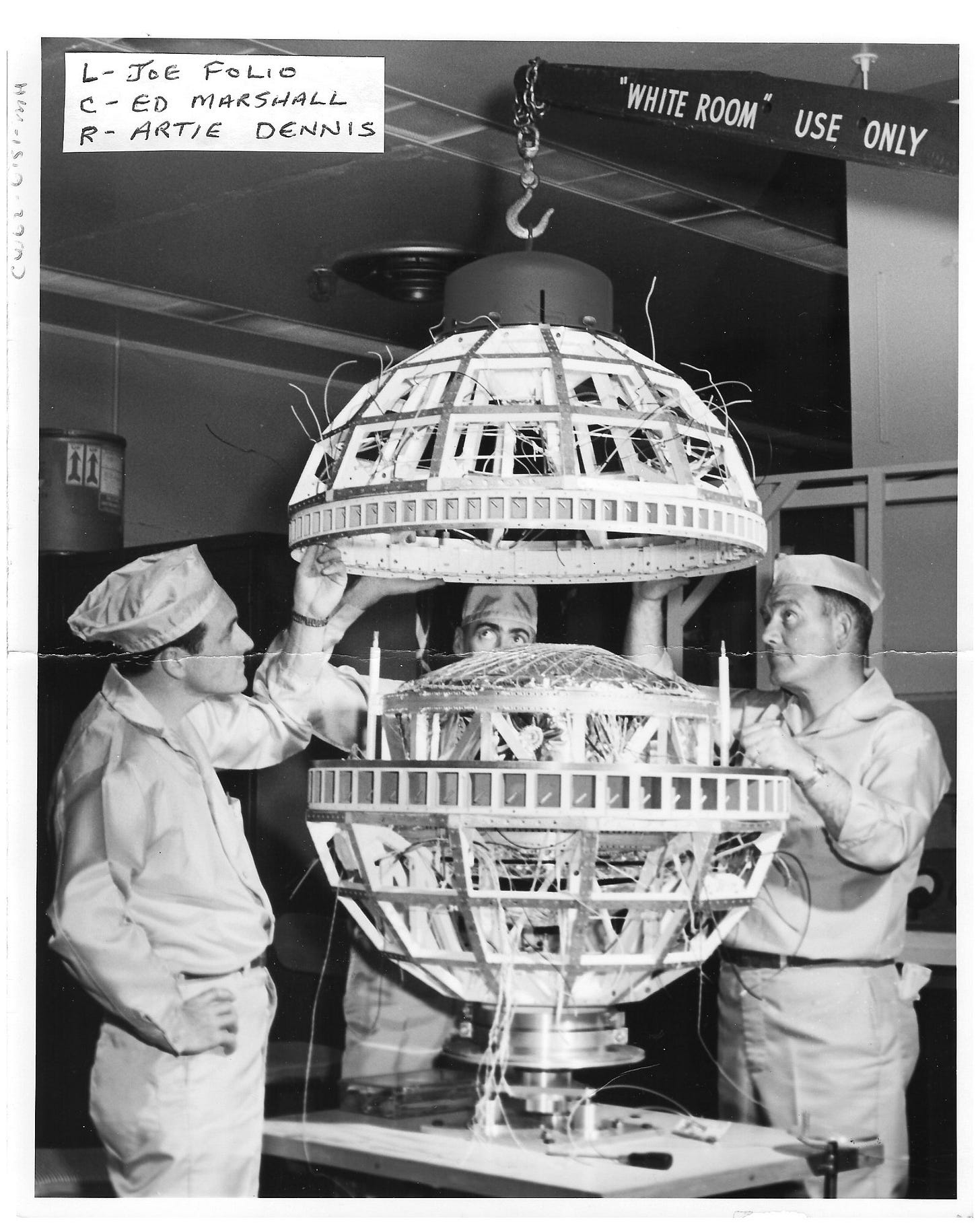

Even in the midst of this epic struggle between superpowers, there was evidence of the emergence of a commercial space economy. In 1962, Telstar 1 — a joint project involving AT&T, Bell Telephone Laboratories, NASA, and international partners — transmitted the first-ever live transatlantic television broadcast via satellite. For the first time, a private company had a financial interest in an orbiting asset. While the event occurred in the shadow of the Apollo missions, it was an early commercial seed in what would eventually grow into the modern space economy.

Following the completion of the Apollo missions, the monolithic approach to managing the U.S. space program began to reveal its weaknesses. The Space Shuttle was designed to provide routine, low-cost access to space through reusability. It was a technological marvel, but economically it fell short. The Shuttle was extremely complex to operate and, tragically, did not meet expectations regarding safety. It demonstrated that a government can dedicate vast resources to achieving a monumental goal, but it is not well suited to providing a sustainable, low-cost transportation service.

A turning point in the development of the space economy emerged from both external and internal sources. Externally, the Ansari XPRIZE offered $10 million to the first private team to develop and successfully fly a reusable crewed suborbital spacecraft. The winner, SpaceShipOne, demonstrated that small, agile, privately funded teams could accomplish goals previously believed to be achievable only by superpowers. This was a major psychological breakthrough that inspired a new generation of entrepreneurs.

From within NASA, change was brought about by necessity. As the Space Shuttle approached the end of its operational life and the need to supply the International Space Station (ISS) loomed, the agency faced a difficult decision. Rather than design and own the next generation of space vehicles, NASA decided to purchase services. Through the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program, NASA acted much like a savvy anchor tenant for a developing area. The agency established the destination — the ISS — and the type of cargo that needed to be transported, but let the private sector determine how it would happen. NASA did not pay based on costs incurred, but instead on milestones achieved. A successful rocket engine firing, the completion of a launch pad, or a successful orbital flight were examples of milestones that earned payment under the COTS program. This single policy shift catalyzed the market for the private space industry. It ignited a burst of private innovation. The new approach encouraged companies to be efficient, to fail quickly, and to innovate continuously at the lowest possible cost, because every dollar a company saved was a dollar it could retain. This act of outsourcing helped transform the last frontier from a government-operated program into a thriving, competitive, and investable economy of companies vying for profits. The competition for prestige between superpowers had come to an end, and a new competition for profit between companies had begun.

The Big Picture: Two Pillars and a Referee

Two massive pillars support today’s space-based economy. The first pillar is the equipment and infrastructure (the “machines”) used to launch from Earth, travel to orbit, or operate in orbit: rockets, thrusters, satellites, landers, and space stations. The second pillar consists of the support industries that provide reliability and profitability: sensors, power electronics, communications systems, training and education, insurance, logistics, and specialized materials for the construction of other components.

Government organizations like NASA, ESA, JAXA, the U.S. Space Force, CNSA, and Roscosmos fund, oversee, and purchase the first copy of most new capabilities needed by these private organizations.

Government organizations can be thought of as both anchor tenants and referees. They create many of the rules and regulations that govern the operation of their own missions and those of others who use their facilities; they ensure that the equipment and services contracted to them are safe; they purchase missions from private companies; and they contract with those same companies to design, manufacture, and/or operate the equipment and services.

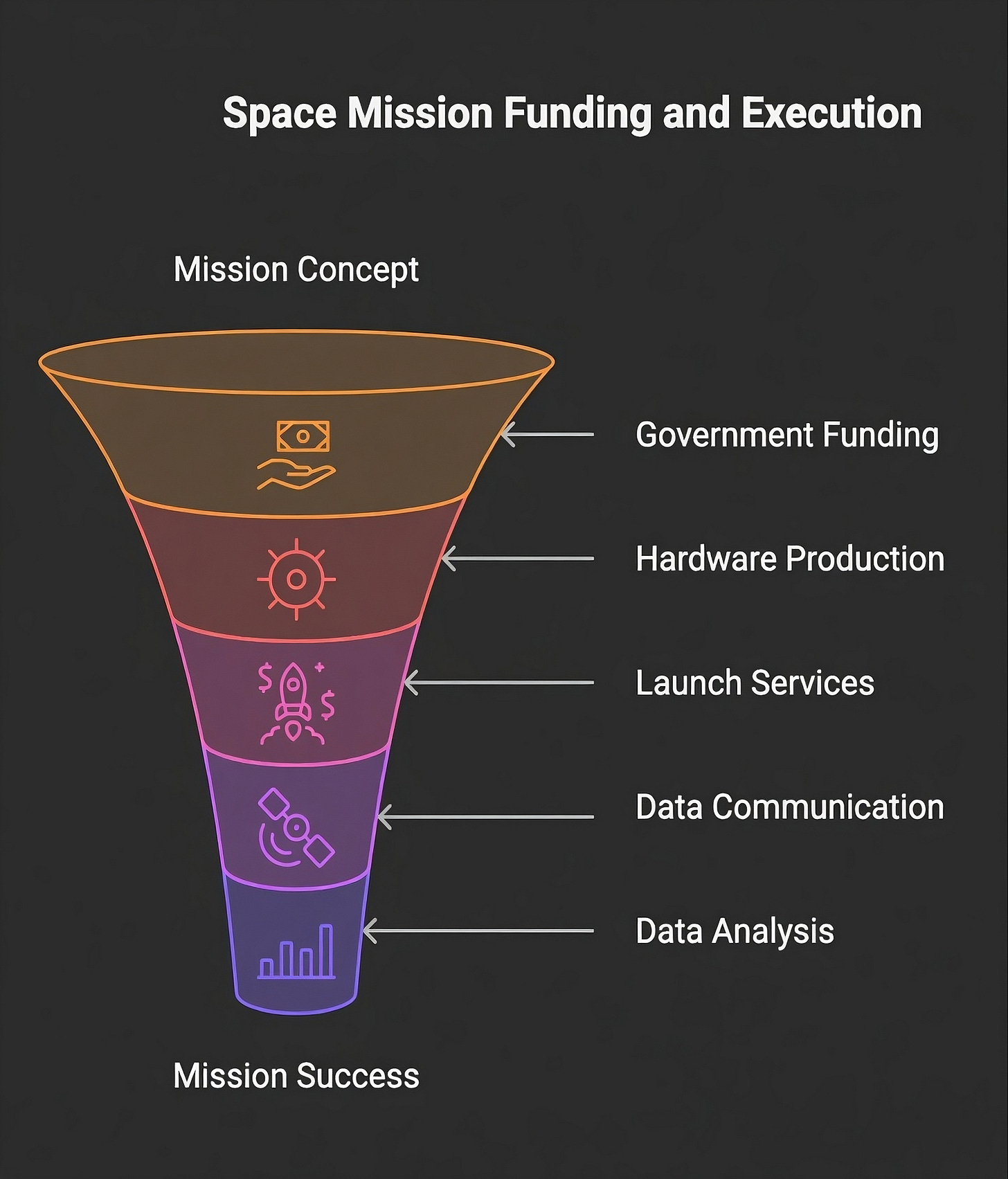

An example of how money flows between all parties in a single mission would be an organization wanting to have something done in space—such as deploying an everyday mapping camera for crop management or a lander to deliver a science package to the Moon. To accomplish this goal, the organization must pay manufacturers to produce the necessary hardware and then pay the launch company to transport that hardware into space. Next, the organization must pay communications providers to transmit the data back to Earth, and finally, the organization must pay analytical companies to transform that data into usable information. Insurance and logistics companies work at each stage to ensure that the process is completed successfully.

Let’s take a closer look at the individual elements involved in the process.

Launch and Propulsion: Opening the Space Sea

Launch is the anchor point of the launch system. SpaceX (private), Blue Origin (private), Rocket Lab (RKLB), and ULA (private) are the captains of this harbor. These companies design and operate rockets, place payloads into a protective cone called a fairing, obtain range clearance, and ignite the engines. Launch costs generally dictate what can happen further upstream: when launch prices fall, a number of new business models become economically viable.